In the late 1970s, psychologist Bruce K. Alexander conducted a groundbreaking experiment that redefined how addiction is understood. Known as the Rat Park study, the experiment demonstrated that addiction is not simply about chemical dependency, but about environment, connection, and mental health. Rats isolated in cramped cages consistently consumed morphine-laced water, while those housed in an enriched, social, and stimulating space—"Rat Park"—mostly avoided it. The implication was clear: addiction flourishes in environments of despair and isolation.

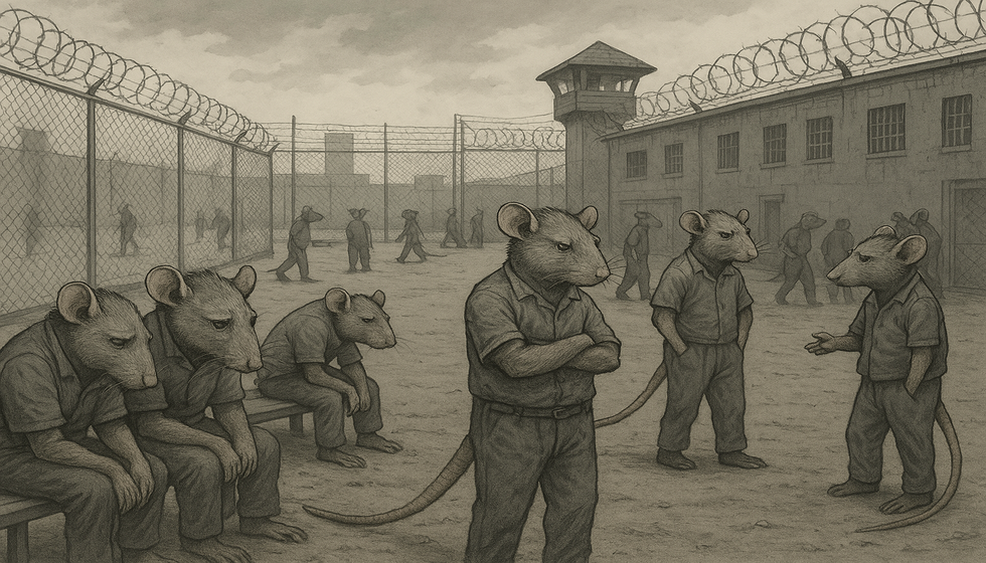

Today, conditions within the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) reflect a disturbing parallel. Over the past two decades, numerous inmate and staff accounts confirm that the BOP has significantly reduced rehabilitative programs, recreational opportunities, and social interaction—replacing engagement with punishment, and hope with monotony. The resulting surge in drug use behind bars is not coincidental. It is the inevitable consequence of the system’s design.

Despair by Design

Over 50% of federal inmates have a history of substance use disorders, according to the Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Statistics. Despite this, many BOP facilities lack access to consistent or meaningful rehabilitation services. In fact, the only formal drug treatment program available—the Residential Drug Abuse Program (RDAP)—is a 9-month program only accessible to inmates within the final 24 to 36 months of their sentence. As a result, the vast majority of incarcerated individuals have no access to treatment for the vast majority of their years in custody.

BOP inmates have reported that even basic educational and vocational programs are limited or inaccessible, and in some facilities, entirely defunded. Recreation has been stripped down to minimal physical movement in overcrowded yards. Visits are sparse and expensive. Communications with family are time-restricted and cost-prohibitive. There are no treatment units, and proposed models such as specialized recovery units remain theoretical.

In effect, the BOP has constructed the equivalent of an endless solitary experiment. Inmates are given the bare minimum for survival but denied the very conditions that reduce the desire to escape into addiction: purpose, engagement, and human connection. In this context, contraband drug use—whether for relief or profit—becomes not a moral failing, but a rational response to institutionalized hopelessness. In fact, the BOP could not have engineered a more perfect environment to encourage drug use—and thus create opportunity for corrupt officers to profit from supplying contraband—if it had tried.

The Illusion of Reform

Proposed ideas such as tiered rehabilitation models suggest an awareness of the problem, but these remain largely theoretical and unimplemented. While such efforts could potentially treat addiction as a rehabilitative rather than punitive issue, they ignore the environmental factors that underlie the problem. As in the Rat Park study, sobriety is unlikely to emerge from sterile confinement alone. Forced abstinence does not equal recovery, and discipline does not foster dignity.

BOP inmates have reported that, even when drug education or counseling sessions are offered, they are often inconsistent, under-resourced, or led by untrained staff. Behavioral incentives are undermined by the broader deprivation of life quality within the general prison population. Without systemic improvements, these treatment models—if and when implemented—risk functioning more as containment than cure.

Crowding and Its Consequences

The average federal prison operates at over 103% capacity. Overcrowding has been directly linked to increased violence, mental health deterioration, and decreased access to rehabilitative services. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, inmates in less crowded facilities report better mental health outcomes and reduced rates of recidivism. The psychological effects of packed living conditions echo the worst outcomes of Alexander’s isolated lab rats—aggression, apathy, and addiction.

Solutions: Building a Real-World Rat Park

If we accept that environmental enrichment reduces addiction, then we must reimagine incarceration with that principle at its core. Rehabilitation must be rooted in dignity, not deprivation. Below are key reforms that draw directly from both the Rat Park study and BOP stakeholder reports:

- Enhanced Access to Digital Engagement: Provide BOP tablets with educational apps, cognitive-behavioral therapy modules, music libraries, documentaries, fitness programs, and interactive games. These tools offer mental stimulation, skill-building, and emotional relief.

- Expanded Commissary Options: A broader selection of healthy food, hygiene products, and comfort items fosters autonomy and boosts morale—factors proven to reduce aggression and improve institutional behavior.

- Improved Fitness Facilities: Equip facilities with updated workout equipment and provide structured fitness programs. Regular physical activity is a critical element in reducing stress, combating depression, and reinforcing routine.

- Restored Social Programs: Reinvest in group education, vocational training, theater, peer mentoring, and family reunification initiatives. Social bonds are essential to recovery and community reintegration.

- Reduced Overcrowding: Implement decarceration strategies and transfer non-violent offenders to community-based programs to alleviate housing pressures. Less crowded spaces reduce tension and provide room for programming and movement.

- Meaningful Incentives for Progress: Create transparent and attainable goals for inmates to earn privileges, transfers to better units, or early release credits through sustained effort and sobriety.

- Environmental Design Reform: Redesign prison spaces to support human dignity—natural light, calming colors, quiet zones, and green space can drastically improve mood and behavior, supported by environmental psychology research.

Ultimately, addiction in prison cannot be solved through surveillance or control alone. As the Rat Park study revealed decades ago, the answer lies in the environment. The question before us now is whether the Bureau of Prisons is willing to make that environment one of rehabilitation—or continue confining people in cages where addiction thrives.

References:

- Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Department of Justice. "Substance Dependence, Abuse, and Treatment of Jail Inmates, 2002." (reaffirmed by later reports)

- Federal Bureau of Prisons. "Residential Drug Abuse Program (RDAP)." bop.gov

- Alexander, Bruce K. et al. "The Effect of Housing and Gender on Morphine Self-Administration in Rats." Psychopharmacology (1978)

- American Psychological Association. "Effects of Overcrowding in Prisons on Inmate Health." APA Monitor